On 12th April, 2025, the UK Parliament passed emergency legislation to take control of British Steel’s Scunthorpe Steelworks.[1] Since the closures at Port Talbot in September 2024, the only active blast furnaces left in the UK are located at the Scunthorpe plant. Without those furnaces, the UK would be the only G7 country unable to make its own virgin steel.[2] The legislation aimed to protect jobs and supply chains, whilst also ensuring access to the high-grade steel needed for infrastructure projects in the Government’s Plan for Growth.[3] However, direct intervention is an unusual action for the government. This blog explains some of the background and related issues, focusing both on the immediate priorities and longer-term considerations.

Credit: Ian Paterson / Planet Scunthorpe / CC BY-SA 2.0

Making steel

Blast furnaces burn iron ore alongside coke (a form of coal) to create pig iron, which is then burned in an oxygen furnace to make virgin steel. Known as basic oxygen steelmaking, it is the primary means of steel manufacture worldwide. The ore is smelted at 1,450°C, then heated further to 1,700°C and blown through with oxygen to reduce its impurities and carbon content. The energy requirements are high, and CO2 is emitted both from the combustion and as a waste gas during purification. Consequently, it is estimated that steel production is responsible for 7-11% of all CO2 emissions worldwide.[4]

The main alternative is electric arc furnaces – these will replace the blast furnaces at Port Talbot in 2027. Without the chemical reaction of the coke, electric arc furnaces cannot remove the oxygen from iron ore. As such, they do not produce virgin (new) steel, and instead tend to be used to recycle scrap steel. Arc furnaces are more versatile in that they can be turned on and off and, being powered by electricity, the energy source is potentially renewable. However, melting steel calls for exceptionally high temperatures (up to 1,800°C) so the energy consumption remains significant and expensive. For context, fully electrified steel production would equate to the electricity demand of Manchester or the output of around 400 on-shore wind turbines.[5]

Historically, the UK was a pioneer in mass-produced steel. In 1875, the UK produced almost 40% of all steel worldwide.[6] The town of Scunthorpe developed around the sites of iron smelting and soon moved into steelmaking. In the interwar period, Scunthorpe’s share of UK steel production rose from 3% to 10%.[7] Seeking to modernise, the government nationalised the industry in 1967. However, in also seeking to protect jobs, the sector suffered from overcapacity and was privatised in 1988, forming British Steel PLC. Production volumes have subsequently declined.

The steelworks at Scunthorpe are still owned by British Steel. However, as of 2020, the owner of British Steel has been the Chinese manufacturer, Jingye Group. Under Jingye’s management the furnaces would have been cooled, possibly cracking the structure through thermal contraction and otherwise rendering them inoperable as the molten iron solidified, blocking the oxygen injectors. Thus, the government intervened.

Credit: PickPik

Wider context

The UK is already dependent on imports for iron ore and coking coal. Notwithstanding this, the loss of the Scunthorpe blast furnaces would be a step further from self-sufficiency – and it is easier to sustain rather than recover the productive capacity, skills and supply chains. This was the prompt for government intervention, i.e., that the Scunthorpe plant is a strategic asset of national significance, even if economically unviable. That viability gap is clearly visible from the UK’s relatively high industrial energy prices[8] and the significant costs associated with decarbonisation. Also, state aid in China makes their steel exports highly competitive.[9]

Steelmaking forms a significant part of the UK’s industrial heritage as well as underpinning many key sectors in the modern economy. The blast furnaces at Teesside, Ravenscraig and Ebbw Vale, once notable on the world stage, have now shut down. Port Talbot, once Europe’s largest steelworks, employing 18k workers at its peak, now only employs 2k – and those are in the refining of imported steel slabs.[10] Across the country, employment in production has fallen from 320k in 1971 to 25k in 2023,[11] although it is estimated that the wider supply chain contains a further 42k jobs.[12] The sudden loss of 2,700 jobs at Scunthorpe would represent a major economic shock, especially given the skills gap in the district, although those jobs are already in a context of long-term precarity.

Scunthorpe’s furnaces will eventually need to be replaced. The suggested alternative, electric arc furnaces, uses less labour, so would still call for a transition for some British Steel workers. In any case, steel manufacturing needs a significant investment for capabilities to be retained, and for those jobs to be protected and sustained.

The UK manufacturing sector is often depicted as being in decline. Yet in almost any ten-year stretch since the 1980s, production has seen an increase.[13] The sector employs a smaller share of the labour pool than it once did, but this can be reframed as modernisation, automation, and specialisation just as much as it can be considered a decline. The same reframing can be said for the subsector of steel manufacturing given it has also suffered from a relative decline in employment terms. Whilst the virgin steelmaking capability and the steelworker jobs are both important, we also need to question if they are capable of driving the productivity and innovation-led growth that the UK needs.

Credit: Mixabest

Steel strategy

The costs of intervention in British Steel will draw from the £2.5bn Steel Fund that was already in place to support the industry. The demand for steel is assured as the material is fundamental in all strategic domains, from the construction of hospitals to building infrastructure to manufacturing ships, tanks and planes. However, given British Steel’s losses of £233m per year,[15] the long-term picture of that industry leader is far from clear. Consider that in 2024 there were around 750 businesses in primary steel production in the UK.[16] So, whilst British Steel occupies a unique position, it is not the only player in the market – there are more jobs at risk than just those at Scunthorpe and the Fund can only stretch so far.

It is worth mentioning that the longer-term trend of output decline is masking a different story. The 2024 figure of 750 businesses in the subsector is a dramatic increase from 115 back in 2010.[17] The increase is in small firms, likely specialising in particular technologies. Consider Sheffield, the Steel City, which has transitioned from mass to specialised production – fewer jobs, but of higher value, and integrated into an economy of advanced manufacturing.[18]

Furthermore, moving to a circular economy and enhancing the UK’s capabilities in relation to green steel could be compatible with losing our ability to manufacture virgin steel. Steel is recyclable – even in the context of manufacturing high-grade components like those used in nuclear submarines – plus, we currently manufacture less than we throw away (5.6m tonnes vs 7-8m tonnes each year).[19] Thus, with effective management of resources this transition may in fact improve national security by relying less on imports – equally, this would help us reach Net Zero as imports engender hidden carbon emissions.

Given the above, it is fair to pose the question of how the Steel Fund should respond and support the industry in the UK. The role of blast furnaces is just one component of that question, and there is a bigger picture of the national Industrial Strategy to consider.

Credit: Neil Theasby

A question of priorities

Before moving on to the key consideration of this blog, it is worth outlining some other considerations in relation to prioritisation and how best to focus limited resources.

The UK’s steel manufacturing landscape is a complex one and our traditional tools of socio-economic analysis don’t point towards an easy solution. Indeed, it is interesting to consider how to value a loss-making asset. In 2016, British Steel changed hands for £1, but by March 2025, the government was willing to offer Jingye £500m to sustain production. It is an asset that costs money; it is an opportunity tied to a responsibility.

It is clear that the government will take a more supportive role in the wider sector. The US’s recent tariff drama signals an end to the era of free trade, and it is increasingly obvious that reliance on imports comes with precarity. Even short of nationalisation, the government will take steps to safeguard its procurement and protect the national interest. Offshore-wind alone will call for 25 million tonnes of steel by 2050.[20]

Keeping the blast furnaces going, or even switching to electric arc furnaces, may seem to have a prohibitive cost – but inaction would potentially be far more expensive. Behind the steelmaking capability, and the 2,700 jobs, there is a wider community at risk. Whilst similarly difficult to quantify, we already know the severity of the consequences they face.

Credit: Pieter de Josselin de Jong

So, what about Scunthorpe?

On the 26th of April, 55k tonnes of blast furnace coke were delivered to the port at Immingham, ensuring continued operation at the Scunthorpe steelworks.[21] Whilst statements implying continuation into the “foreseeable future” were welcomed by workers, the economic fundamentals of the industry have not changed and so the commercial challenges facing the steelworks remain. Even a pivot to more modern manufacturing processes are likely to result in significant jobs losses and painful restructuring. Therefore, it is also worth reflecting on the wider place-based impacts and localised community effects.

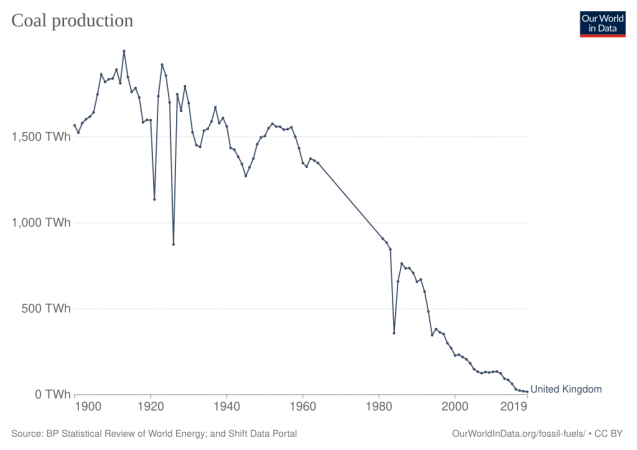

Scunthorpe’s problems are already being played out at Port Talbot, where thousands of workers are being forced to search for a new job, risking the community feeling left behind.[22] More broadly, this is another chapter in the UK’s story of deindustrialisation. We can draw a parallel between the scenario at Suncthorpe and the demise of the UK’s coal mining industry. With that in mind, this week I spent some time in the SQW archives. Though it was before my time, the company evaluated the coalfields regeneration programmes, and it is not hard to transfer some of the learning to today’s predicament.

From the 1950s, coal production was in freefall, coming to a head with the failure of the 1984-85 strike and the ensuing pit closures. In 1998, in coalfield towns, almost a quarter of male employment was lost. At the time of SQW’s evaluation (2006), despite years of regeneration efforts, many of the coalfield sites remained at a disadvantage relative to the rest of the country. SQW’s research found that those sites needed more sustained regeneration than expected and that the “poor health, low educational attainment and the lack of an enterprise tradition” made it difficult for those left unemployed to make the most of job opportunities that came their way.

The loss of jobs was a short-term shock but the impact was persistent, leading to higher rates of worklessness and engrained pockets of deprivation. The anchor industry that had characterised those places was replaced by a different legacy. For nearly a third of the population, the pit closures remained in their perception, particularly as a reason for long-term unemployment. Regeneration went some way to improving perceptions of the former coalfield areas, but it was not enough for those who moved away, further eroding the sustainability of the communities.

Locally, the coal miners were a bigger proportion of the population than the steelworkers are in Scunthorpe, but the parallel remains. There is a risk of inter-generational deprivation with the disappearance of a firm that employed your father and grandfather (or grandmother, as the Women of Steel Statue reminds us).

Beyond continued support, the recommendation at the time was to focus on resource allocation so that delivery by mainstream providers would be aligned with the particular needs of the most disadvantaged areas. For example, reshaping attitudes towards educational attainment. For steelworkers in Scunthorpe, it would also be wise to pay attention to lessons learned at Port Talbot by the Tata Transition Board, and more widely at Teesside, Ravenscraig and Ebbw Vale.

Conclusion

The decision on how to proceed with Scunthorpe's steelworks will reflect the UK's broader industrial strategy. It will involve tough choices about where to invest, how to innovate, and how best to support communities through transition. The need to embrace new, more sustainable methods of production must be managed carefully to mitigate job losses and the erosion of local communities – ideally as part of a comprehensive approach to place-based economic development framed by effective multi-agency partnership working. Learning from previous industrial restructuring can offer helpful insights in how to respond effectively to major plant closures and/or disinvestments – such as those within the UK’s steel industry. However, a key takeaway is that it can take decades for local economies and communities to recover and a long-term commitment is essential.

Reference List:

[1] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/59-01/0221/en/240221en.pdf

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c5y66y40kgpo

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-acts-to-save-british-steel-production

[4] https://www.sustainable-ships.org/stories/2022/carbon-footprint-steel

[5] 5.6 million tonnes of steel at 450 kWh/tonne is 2.5 TWh, relative to Manchester’s consumption of 2.4 TWh. Based on https://www.uksteel.org/ and https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/regional-and-local-authority-electricity-consumption-statistics

[6] Carr, J. C. and W. Taplin; History of the British Steel Industry Harvard University Press, 1962. pp. 164–66 cited in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_steel_industry_(1850-1970)

[7] Pocock, D. C. D. (1990), Ellis, S.; Crowther, D. R. (eds.), "The Development of Scunthorpe", Humber Perspectives : A region through the ages, pp. 332–344 cited in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scunthorpe_Steelworks

[8] To give an example, in Germany, electricity costs for heavy industry is around two-thirds that of the UK https://reports.electricinsights.co.uk/q4-2024/why-are-britains-power-prices-the-highest-in-the-world/

[9] https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/04/subsidies-to-the-steel-industry_71693a1e/06e7c89b-en.pdf

[10] Similarly to Scunthorpe’s ownership by a Chinese manufacturing group, the steelworks at Port Talbot is owned by the Indian conglomerate, Tata. The firm has a £1.25bn investment to replace the Port Talbot’s blast furnaces with electric arc furnaces. https://www.tatasteeluk.com/corporate/news-tata-steel-will-proceed-with-its-£1.25-billion-investment-to-build-a-state-of-the-art-electric-arc-furnace-in-port-talbot

[11] This is for the narrow definition of the steel industry, which includes manufacture of iron and steel but exclude downstream production of pipes and other products. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7317/CBP-7317.pdf

[12] https://www.uksteel.org/steel-news-2025/new-management-signals-brighter-future-for-british-steel

[13] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/output/timeseries/k22a/diop

[14] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2024/11/05/the-productivity-boom-in-the-british-car-industry-benefited-workers-with-a-caveat/

[15] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c5y66y40kgpo

[16] UK business counts, ONS

[17] This is based on UK Business Counts data, which do not go back any further than 2010.

[18] Whilst it is not an SME, Sheffield Forgemasters is a good example of specialism in bespoke steel castings and forgings. The company uses electric arc furnaces to produce some of the highest grades of steel as needed for defence contracts, and it is able to produce the world’s largest castings, pouring 600 tonnes of molten steel. https://www.sheffieldforgemasters.com/news-and-insights/news/02/sheffield-forgemasters-pours-a-world-first-ultra-large-casting/

[19] https://edconway.substack.com/p/does-it-really-matter-if-we-cant

[20] Estimate by LumenEE, cited in https://www.uksteel.org/steel-news-2024/uk-steel-sector-calls-on-government-to-unlock-multi-billion-pound-opportunity-in-procurement-reforms

[21] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/coke-shipment-keeps-british-steels-blast-furnaces-burning

[22] https://news.sky.com/story/port-talbot-how-steel-town-is-grappling-with-life-changing-loss-of-more-than-2-000-jobs-13345631