Unlocking the potential of heritage: A catalyst for regeneration and growth?

Exploring the benefits and challenges associated with heritage regeneration

By Annie Finegan, September 2025

Heritage regeneration involves not only the preservation of the heritage environment but revitalising it to meet the needs of today’s society and economy.

This blog discusses the benefits and challenges associated with heritage regeneration, using the example of a heritage regeneration initiative, Historic England’s Heritage Action Zones programme, which SQW recently evaluated.

The benefits and challenges of heritage regeneration

The heritage environment can – and in many places does - make a place feel special. It gives unique character, shapes the streets we walk through and can anchor communities in their shared history.

Heritage brings enormous social and wellbeing benefits to local people and visitors (What Works Centre for Wellbeing, 2019). A well-preserved environment is often a symbol of pride, reflecting a place’s identity and story, and linked to people’s overall life satisfaction. Community wellbeing benefits include the use of heritage buildings as venues for cultural events and other activities: in many places they help foster a sense of belonging, ownership, and social connection. Recent research has shown that 80% of people think that local heritage makes their area a better place to live.

Heritage is also linked to economic outcomes. At a national level, England’s heritage sector made a contribution of £15.3bn in GVA to the economy in 2022 and supported the employment of over 523,000 workers (Historic England, 2024a).[1] Locally, heritage can be the cornerstone of a thriving visitor economy, drawing tourists, supporting town centre businesses and creating jobs (Historic England, 2024b).

However, despite the potential benefits heritage can bring to a place and its people, the role of heritage is not always straightforward and positive.

First, the fact that heritage is tied to a place’s belonging and identity can be controversial, not least because the heritage environment can be a product of historical power dynamics, such as colonialism, conflict and oppression.

Secondly, how the heritage environment is presented, the scope to improve it and the short-term priorities for action vary from place-to-place. The heritage environment in industrial urban areas has struggled in the context of present day socio-economic challenges, in comparison to more obvious, well-established visitor destinations where the heritage environment takes centre stage.

Heritage regeneration in today’s context

Against this complex backdrop, Historic England, the government agency that champions heritage, has a key role in drawing attention to opportunities for re-invention as well as to the significance of the legacy.

‘Historic England protects and brings new life to the heritage that matters to us all, so it lives on and is loved for longer’ (Historic England)

Resources are inevitably limited against the scale of evident need and potential demand. The agency must protect the historic environment through cost-effective renewal, while ensuring that the results are accessible, relevant, and meaningful in the context of current socio-economic conditions. The challenge is three-way: to identify and protect what is most valuable; to help create sustainable uses in the context of specific local challenges and to show positive results from this activity as quickly as possible.

This has led to the development of initiatives to focus and catalyse heritage renewal at the local level. These aim to highlight significant opportunities, engage partners, enable resource and stimulate complementary actions from wider stakeholders. These require careful, well-informed design if they are to produce results of value in the longer-term for the communities and local economies in which they are set.

The Heritage Action Zones programme

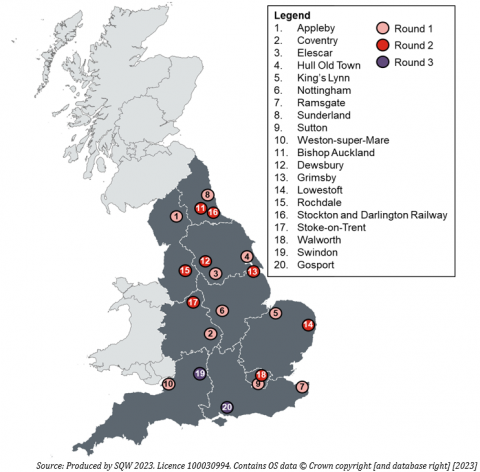

The Heritage Action Zones (HAZ) programme, launched in 2017, drew on Historic England’s experience in working in local places, initially with a remit focused on realising the value of this potential in the north and midlands. A total investment if £15.7m over four rounds, from Historic England made available through its sponsor, the Department for Culture Media and Sport enabled work in 20 locations. The scale and form of this varied substantially: in some places it directly complemented assistance under the (more widely spread but also more spatially focused) Historic High Streets initiative (HSHAZ). The HAZ programme aimed to support local authorities to unlock the ‘untapped potential in places that are rich in history and historic fabric to help them thrive and improve quality of life for communities and businesses’ (Historic England).

Each HAZ sought to address locally specific challenges through one or a mix of three activities:

- Research investigations into a building or asset such as feasibility work, planning, technical research, listing review, and strategy development

- Capital works focused on selective restoration and conservation or conversion of heritage assets, alongside public realm improvements

- Community and engagement activities to promote understanding, management and conservation or conversion of heritage, delivery of training, and promotion of the HAZ.

Given the wide scope of different types of places and the different forms that guidance and intervention might take to stimulate rather than to directly deliver major works, there was a real need to review what had worked and in what circumstances. This spanned the contribution to changing understanding and the extent to which different involvements in different local places had improved confidence and created potential opportunities for other private and public investment in the longer term. These impacts might generate a ’virtuous spiral’ bringing more substantial socio-economic benefits to the locality – but what evidence could be gathered and analysed to show how whether this was realistic?

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of the HAZs

Learning from SQW’s evaluation of the HAZ programme

SQW was commissioned, while the programme was still underway, to evaluate the results and assess learning for any similar future interventions. Our assessment had to take into account the effects of Covid-19 lockdowns, changing local contexts and opportunities, wider shifts in behaviours and markets – all of which affected early outcomes and made attribution a matter of rounded assessment rather than statistical measurement. But we found evidence for beneficial early impacts in four key respects, all relevant to the ambitious aims of a relatively small-scale programme delivered at a particularly challenging time.

- Revitalised historic environments. The repair and restoration of heritage buildings have significantly enhanced the character and appearance of HAZ areas, setting a strong precedent for future regeneration efforts and reducing the overall risk to the historic environment.

- Greater heritage capacity in local authorities. Research and listing activities have enhanced understanding of heritage assets, including how best to manage and utilise them. This has led to greater strategic focus on heritage in local authorities and better informed decision making around regeneration and heritage.

- Attracting significant further investment. The programme has contributed to local authorities securing additional public or private funding, enabling the continuation heritage-led regeneration beyond the HAZ programme.

- Greater community awareness of, and engagement with, heritage. Through events and volunteering opportunities, the programme has brought local communities together, helping to foster a stronger appreciation of heritage, sense of ownership and social connection.

A key lesson is that interventions need to be flexible. Understanding the local context is crucial, to build on what has already been done, help shape a shared vision for the future and build ‘progressive local coalitions’ to pursue realistic short-term initiatives as well as the longer-term goals. Historic England’s place-based interventions supported this in key areas: through research, in generating momentum through underpinning capital programmes and in building momentum for ongoing local activity. This momentum will be critical to longer-term achievement: it is based on maintaining capacity to help realise ambitions to respond to new economic, social and cultural challenges, bringing the confidence to seek and leverage new opportunities for long-term change.

Figure 2: The Stage Door and Albert Inn in Weston-Super-Mare, Hope Town Museum in Darlington, including Goods Shed, gift shop and outdoor play space (Left to Right), all restored with Historic England funding

Figure 3: Kennedy’s Sausage Shop (Left) and St. Peter’s Church public realm (Right) in Walworth enhanced with Historic England funding

[1] The ‘heritage sector’, as defined for this purpose, is made up of diverse set of industries and therefore includes ONS sectors we might typically think of as relating to heritage such as libraries, archives and museums, as well as other parts of other ONS sectors such as construction and leisure.