An office with a view

Observations and questions on regeneration in Stockport.

By Donald Ross, January 2024

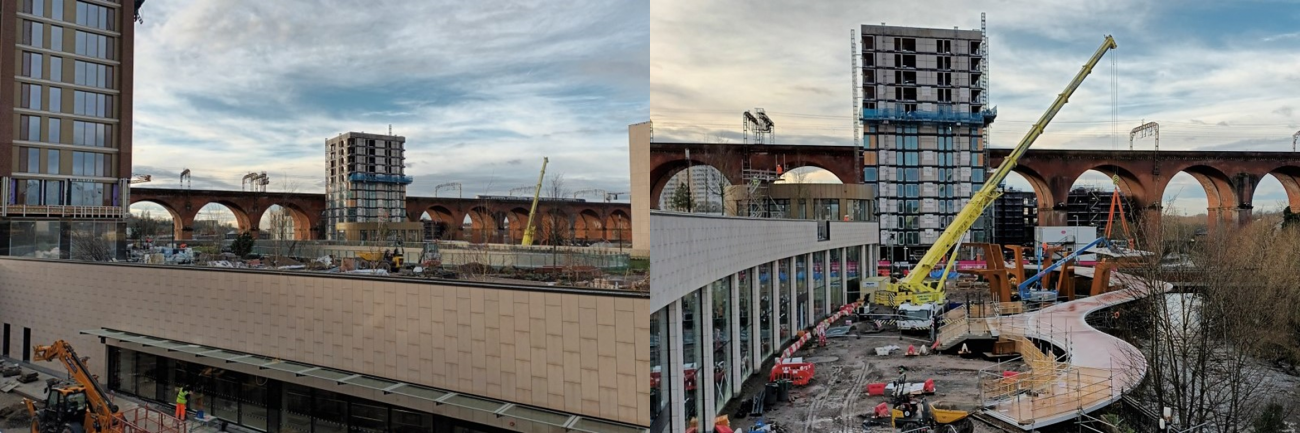

Our office window looks out into central Stockport and gives us a great view of the regeneration efforts across the town. This blog explores why these are relevant on a bigger stage and asks how we can know if they’ve been successful.

“Stockport is renowned throughout the entire district as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes, and looks, indeed, especially when viewed from the viaduct, excessively repellent.”

Not the words of an online troll in 2024, but rather those of Frederick Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England. Just over 100 years on from its publication, industrial scenes with chimneys belching smoke featured prominently in L.S. Lowry’s paintings of Stockport in the 1950s. And as recently as 2018, the “excessively repellent” phrase still held for some architectural critics who gave the Red Rock leisure complex the Carbuncle Cup in 2018.

Now almost 180 years on from Engels, the North West town of Stockport is getting used to receiving more positive coverage. This ranges from a, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, dubbing as “the new Berlin” through to The Sunday Times’ Best Places to Live list declaring that Stockport has “has reinvented itself as a funky, family-friendly alternative to Manchester’s Northern Quarter.” There are regular updates on residential and commercial schemes being proposed, work starting on site or being completed. There is certainly a sense of momentum building.

Declaring an interest

SQW is also playing a part in Stockport’s regeneration, providing jobs and services. Now that we’re back in the office post-Covid, we are able – once again – to buy our lunches from RACK, eat at the monthly Foodie Friday, and compete in Doug’s weekly pub quiz. Perhaps more fundamentally, many of my colleagues and I live in or near Stockport.

Pioneering the Mayoral Development Corporation approach

But why should the wider population be interested in Stockport? Beyond the hype about the latest bar or restaurant to open in the increasing popular Underbanks area of the town, Stockport is an interesting example of trends in economic development taking place across the UK.

As a starting point, the problems that the Council is seeking to tackle are all too familiar to other towns and cities across the UK. They stretch from the post-industrial legacy of, in Stockport’s case, the textiles and engineering activity described by Engels, through to declining high streets and empty units left by the closures of Debenhams, British Homes Stores, and other once-familiar names.

The public sector has been prominent in regeneration efforts here, first through the Council and, since 2019, an ambitious Mayoral Development Corporation (MDC) – a model that harks back to the urban development corporations of the 1980s. We often comment on the importance of strong leadership in our project work, and the MDC is a good example of this as it was originally chaired by Lord Bob Kerslake, the former head of the civil service. Cllr Mark Hunter, Leader of Stockport Council, commented that “with a contacts book second to none, Bob was a high profile and powerful ambassador for the transformation of our town centre and our ambitious regeneration programme.”

Stockport is one of the first places to create an MDC, partly because Stockport sits within Greater Manchester which was one of the earliest Mayoral Combined Authorities. No doubt other Mayoral Combined Authorities, and those responsible for establishing governance structures for Freeports and Investment Zones, will be looking to learn from Stockport’s experience.

Stockport’s MDC covers the ‘town centre west’ area of 52.6ha (130 acres) and aims to deliver on a Strategic Regeneration Framework that calls for the creation of “Greater Manchester’s newest, greenest and coolest affordable urban neighbourhood”. The SRF anticipates that the area could accommodate 3,500 new homes and 1,000,000 sq ft (c.93,500sqm) of employment space. The MDC’s draft Strategic Business Plan 2023-2028 states that “Over 1,100 new homes and 170,000sq ft [c.15,800sqm] of grade A office space [are] completed or in construction.” An encouraging start for what the SRF notes could be a 20 year project.

The two flagship developments within the MDC area are arguably the new grade A offices at Stockport Exchange adjacent to the train station, and the redevelopment of the old bus station into Stockport Interchange with a modernised bus station and rooftop park, as well as around 200 new apartments.

Pursuing a mix of strategies on brownfield sites

Stockport has not put all of its eggs into the MDC basket though. Both within and outside the MDC boundary, Stockport has also had success in securing funding from DCMS, Homes England and Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), often through competitive processes. Even more encouragingly, the private sector is becoming increasingly involved. Developers such as Muse, Capital & Centric, and the English Cities Fund are bringing their expertise to the town.

This has created a mix of development activity across the MDC area and beyond, with transport, residential, retail and commercial developments completed, underway or planned. The mix of public funding also means that the regeneration efforts have different emphases, such as the aforementioned Merseyway Innovation Centre as well as a Creative Campus programme, heritage led regeneration in the old town and a “library, community and education centre” called Stockroom.

Stockport is also notable for its use of brownfield sites. Given debates about housing shortages, Stockport is an interesting case study of converting old mills – such as Weir Mill which is said to have inspired Lowry - and other vacant properties into town centre homes. There has also been a flexible approach in the pedestrianised town centre where the old Marks and Spencer store is now a modern office development, and the Merseyway Innovation Centre occupies another former retail unit.

In short, there is a lot of activity occurring in a relatively confined space. And at least one of these activities will be relevant to every other town and city with regeneration plans across the UK. Which ones will prove most successful in Stockport?

Location, location, location

Stockport is not developing in isolation. The town’s connectivity to Manchester is used as part of the sales pitch across almost all of the schemes mentioned above. This isn’t a new factor though – the Grade II* listed railway viaduct that dominates Stockport’s skyline opened as long ago as 1840. What has changed is that the places connected by the viaduct, especially at the central Manchester end, are now increasingly attractive. With Manchester booming and many prime development sites already taken, developers appear to be seeing Stockport as an exciting prospect. To what extent, then, is Stockport’s regeneration benefitting from a spillover of Manchester’s own urban renaissance? And indeed, how might Stockport and its growing supply of town centre housing benefit businesses based Manchester?

As well as Stockport’s economic geography and linkages to elsewhere, there is also an important administrative geography dimension to the story. As noted above, it is Stockport’s location within the GMCA area that allowed the MDC to be created. The border with the Cheshire local authorities is only six miles or so to the south of Stockport but, because of the differing levels of devolution across England, Cheshire towns cannot establish MDCs. GMCA, through programmes such as its Brownfield Housing Fund, also provides a source of finance to help unlock specific schemes in Stockport.

Questions for the future

It is too early to declare Stockport as a regeneration success story – and, perhaps more philosophically, can anywhere ever claim to have tackled all of its socioeconomic issues? New technologies emerge, national and international (political) contexts change, and the entire system can be disrupted by external shocks, as Covid-19 unfortunately demonstrated all too clearly. The imperative of adapting to change is, after all, why Stockport is in the position of needing regeneration.

In watching from our office window, we’ll be paying particular attention to whether the:

- current momentum is sustained despite challenging macro-economic conditions and budget constraints for the Council and other public sector bodies.

- mixture of different interventions delivered at a similar timescale in a tightly defined geographic area leads to benefits that are ‘more than the sum of the parts.’

- property development schemes are successful in commercial terms. How quickly will the space be filled?

- property development schemes are successful in economic development terms. What type of companies are taking space, and what quality of jobs will they create? It will also be important to understand where those companies come from – is the new space enabling company growth and/or attracting new firms into Stockport, or will it mainly displace occupiers from one part of Stockport/Greater Manchester to another without a net change in economic activity levels?

- existing population in the town centre and adjacent areas benefit from these physical developments. Will they be able to afford the new housing?[1] Will they have the right skill levels to access the new jobs? Has the public sector created the correct revenue funding streams to support the local population and business to make the most of the physical developments?

A much harder question to answer through external observation is about the role of the MDC. To what extent is it directly delivering or catalysing development that otherwise would not have happened? Or would not have happened at such scale or pace? How far do any catalytic effects of the MDC spread outside its formal boundaries? Has the Town Centre West MDC encouraged developments across the wider town centre area?

From an evaluator's perspective, these are all very interesting questions. None are straightforward to answer. What place-based evaluation techniques could be used provide robust evidence? And could similar methods be used to understand whether the mix of regeneration strategies across Stockport is delivering benefits that are 'more than the sum of the parts'?

We know that regeneration is a difficult and long-term endeavour. Changing perceptions of an area amongst residents and businesses, as well as those from outside, is part of the process. Will Stockport shake off its negative reputation as the dusky, smoky hole of Engels and subsequent post-industrial decline to transition successfully into a new urban neighbourhood? Whatever happens, we’re committed to being part of Stockport’s ongoing regeneration.

[1] With the limited supply of housing in the town centre pre-MDC intervention, the risk of pre-existing town centre occupiers being ‘priced out’ as a result of any future gentrification is relatively low